For the secondary history teacher, teaching reading and writing can seem like pretty formidable tasks. Most of us were never trained how to teach students to read and have little idea how to go about it. We often think of all the historical skills and content that we are supposed to cover, and wonder how we might ever fit in teaching reading and writing as well. Holding history students and their teachers accountable to the Common Core literacy standards at first glance appears to be assessing what ought to be taught in English classes.

However, a closer examination of the Common Core Reading Standards for Literacy in History / Social Studies 6-12 reveals many standards that describe exactly what historians do. For example: the very first standard for Grades 6-8 students (RH1) reads: “Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources.” Historians analyze primary and secondary sources to make interpretations of historical events, and they support their interpretations with specific textual evidence. Teaching students how to identify, use and cite specific evidence from texts is one of the major objectives of history instruction. Other “historical” standards (for Grades 6-8) are:

RH6: Identify aspects of a text that reveal an author’s point of view or purpose (e.g., loaded language, inclusion or avoidance of particular facts.)

RH2: Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of the source distinct from prior knowledge or opinions.

RH9: Analyze the relationship between a primary and secondary source on the same topic.

Then there are other standards which do not carry such a direct relationship to the work of historians, but are vital to helping our students understand the texts we place in front of them. These are components of the reading process that we teachers do automatically, but which confound many of our students. For example, RH4 says: “Determine the meaning of words and phrases as they are used in a text, including vocabulary specific to domains related to history/social studies.”

Pretend you are an 8th-grader and read the following passage:

Charlotte Forten Grimke’s Journal

Another day, one of the black soldiers came in and gave us his account of the Expedition [up the St. Mary’s River]. No words of mine, dear…can give you any account of the state of exultation and enthusiasm that he was in. He was eager for another chance at “de Secesh.” I asked him what he w[ou]ld do if his master and others should come back and try to reenslave him. “I’d fight um Miss, I’d fight um till I turned to dust!” He was especially delighted at the ire [anger] which the sight of the black troops excited in the minds of certain Secesh women whom they saw. These vented their spleen [anger] by calling the men “baboons dressed in soldiers’ clothes,” and telling them that they ought to be at work in their masters’ rice swamps, and that they ought to be lashed to death. “And what did you say to them?” I asked. “Oh miss, we only tell um ‘Hole your tongue, and dry up.’ You see we wusn’t feared of dem, dey couldn’t hurt us now. Whew! didn’t we laugh . . . to see dem so mad!” The spirit of resistance to the Secesh is strong in these men.

Secesh – nickname and sometimes insult for the Confederate soldiers (urban dictionary)

Although this primary source text would be tough for most 8th-graders to understand, helping them decode it would give them access to three unfamiliar perspectives in a vivid, engaging narrative. How would the teacher help 8th-graders to understand and analyze this text?

Before students do any analysis, they need to understand what the text says. Most classes have at least one or two precocious students who can tell you exactly what the text means after examining it for 30 seconds, but the rest of the students need much more time to examine the text itself. They need an activity which makes them look carefully at the text for an extended length of time before they have to answer questions about the meaning. Taking them through a literacy activity is especially useful because it helps them to understand the structure of the sentences and the unfamiliar vocabulary.

For the Forten passage, a teacher might ask students to circle all the pronouns in the text and then to fill in a chart giving the antecedents. Since pronouns are particularly difficult for English Learners, and this text employs pronouns from a dialect which they have likely never seen in print, the activity will aid their comprehension. Completing it will take time, but during that time, they will also be digesting the text. The teacher can follow up by asking them to identify perspective.

Another possible literacy activity is sentence deconstruction. Take the most difficult (or the most crucial) sentence of the text and break it down for students in this chart format:

| Time Marker or Connector | Historical Actor | Verb or Verb Phrase | What? | Questions or Comments |

| He (the black soldier) | was especially delighted at | the ire | Who was angry?What sight excited their anger?

Who was delighted?

|

|

| which | the sight of these black troops | excited | in the minds of certain Secesh women | |

| whom (the Secesh women) | they (the black troops) | saw. |

After going through this chart as a whole class exercise, the teacher might ask students to read the rest of the passage aloud, while he or she explains the meaning or defines vocabulary. At the end, the teacher might ask, “Why was the black soldier delighted?”, “Would you have been delighted in his place?”, and “Why do you think he felt that way?”

If this seems too much like an elementary grammar lesson, consider how similar this strategy is to the research methods of the historian. Looking closely and repeatedly at the meaning, the structure of sentences, and the nuances of historical texts is one of the fundamental tools of the historian. The history teacher is modeling the behavior of historians while helping students understand – and then analyze – difficult primary texts.

Source for the text passage: Charlotte Forten Grimke, The Journal of Charlotte Forten: A Free Negro in the Slave Era (New York: Collier Books, 1961), p. 164.

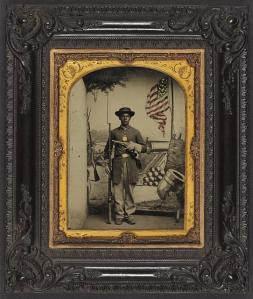

Source for photo: Unidentified African American soldier in Union uniform with a rifle and revolver in front of painted backdrop showing weapons and American flag at Benton Barracks, Saint Louis, Library of Congress, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2010647218/Missouri

Filed under: General | Leave a comment »